A Unified Platform for Automated Processes and Optimized Outcomes

The GovOS software platform offers a suite of solutions delivered on a cloud platform that enables local governments to automate manual work, streamline operations, and provide seamless access to resources and information, and deliver cutting-edge services to businesses and residents.

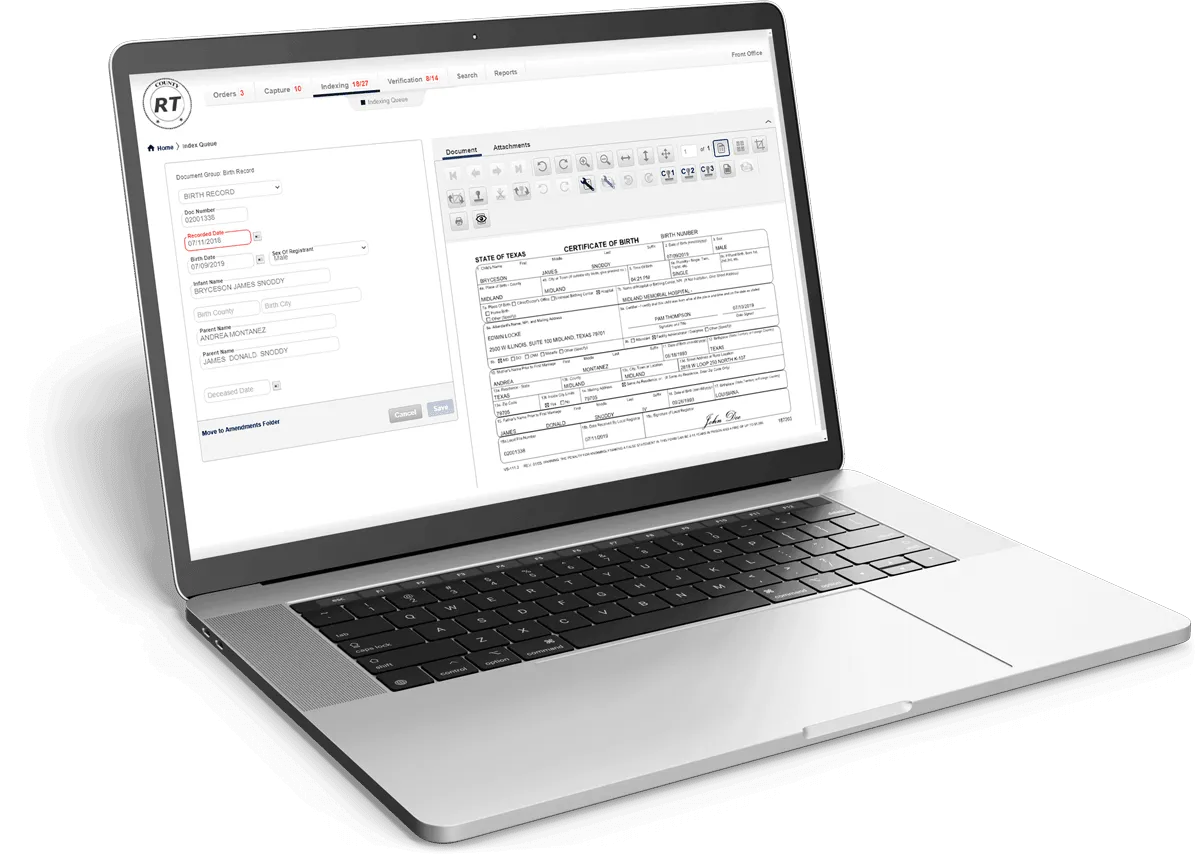

Public Records

Efficient Document Management

Built with the record at the center to ensure access, the GovOS Public Records Suite harnesses the cloud to empower staff with streamlined transactions, delivering a seamless customer experience. Optimized for ease, our solutions simplify data capture, processing, and retrieval, guaranteeing transparency and universal access. Leverage unparalleled search functionality to allow staff and citizens to efficiently find essential information anytime, from anywhere.

Related Products

Land Recording

Land Records Management that is secure and streamlined with self-service access.

Vitals Recording

A secure, digital system for governments to manage vital records.

Public Record Access

Government records search engine for official public records search.

“The GovOS system gives us the ability to create additional pathways to the next generation.”

John F. Warren

Dallas County Clerk, TX

Licensing & Registration

Effortless Business Licensing and Registration

Optimize every aspect of business licensing and registration to empower your business community and enhance operational efficiency—combining all general and specialized business applications and renewals into one unified system, enabling multi-departmental workflows, and offering a 24/7 business portal for effortless compliance and unparalleled service.

Related Products

Business Licensing

Automate and manage business license applications, renewals, and payments in one system.

Short-Term Rental Registration

Efficiently manage short-term rental compliance, from registration to fee collection, within your jurisdiction.

Professional Licensing

Simplify the issuance and maintenance of professional credentials, ensuring requirements are met with ease.

“We have been using GovOS Business Licensing for several years now. We’ve had several staff member changes, but I never have to worry about sales taxes and licensing – even with staff turnover. With GovOS Business Licensing, this revenue collection just 'goes' without me worrying about a thing.”

Renae Gustine

Finance Director, Town of Carbondale, CO

Tax & Compliance

Process Modernization to Revenue Maximization

Effortlessly combine all tax processes in a single, intuitive system, equipped with a 24/7 self-service portal. Free staff from manual tasks to focus on strategic initiatives. Benefit from real-time collections, comprehensive reporting, and automated workflows designed to meet the unique needs of state and local governments.

Related Products

Business License Tax

Streamline business tax filings and payments, ensuring accurate and timely compliance.

Tax Filing

Increase your revenue stream with tax collection software.

Lodging Tax

Gather short-term rental tax revenue from online travel agents (OTAs) and other bulk filers

“Even though the number of accounts has increased, we’ve not had to increase the time our personnel spends actively going through the accounts, collecting taxes, and preparing enforcement proceedings.”

Falin Ivy

Board Services Agent, Okaloosa County, FL

Cloud Platform

Foundation for Innovative and Modern Experiences

The GovOS Cloud Platform enables jurisdictions utilizing GovOS solutions to easily deploy new features and streamline operations.

Related Products

GovOS Pay

A Payments Solution Integrated with GovOS Suites

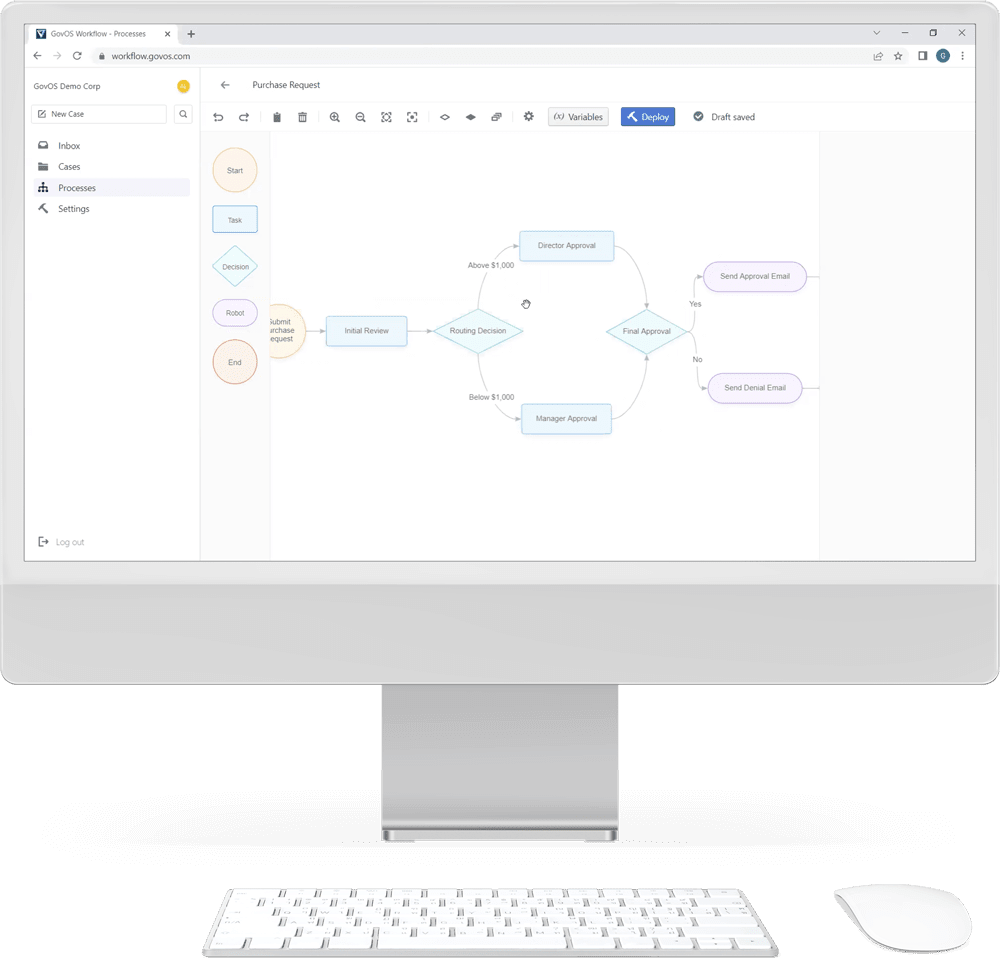

Application Designer

Build the ideal digital process for you, your team and your constituents.

ID Verify

Secure, efficient, and fraud-resistant identity verification.

Agencies Nationwide Trust GovOS

Reimagine the Government Experience

Learn what makes GovOS different. Transform the way you interact with businesses and citizens.